The Ethical Boundaries of AI: Can Algorithms Ever Be Truly Unbiased?

Explore the ethical boundaries of AI algorithms and the challenge of creating truly unbiased artificial intelligence. Dive into machine learning bias and its impact on our technological future.

Introduction: When Math Mirrors Society

From credit scores to courtroom bail decisions, artificial intelligence now whispers suggestions—or shouts verdicts—into the ears of human gatekeepers. The promise is seductive: replace fallible intuition with cold, hard data. Yet headlines keep reminding us that algorithms can be racist, sexist, and classist. Is an unbiased algorithm a mathematical impossibility, or can we code our way to fairness?

1. Bias Isn’t Just a Bug—It’s a Feature

Machine-learning models learn patterns from historical data. When that data encodes decades of red-lined neighborhoods or male-dominated boardrooms, the algorithm dutifully memorizes the injustice. In 2019, a healthcare algorithm was found to favor white patients for additional care because it used past healthcare spending as a proxy for need—a metric skewed by unequal access.

The uncomfortable truth: bias can be statistically “optimal” if the objective is raw prediction accuracy. Fairness, therefore, must be an explicit design requirement, not an afterthought.

2. Defining Fairness: A Tower of Babel

Computer scientists have cataloged over 21 mathematical definitions of fairness. Some demand equal false-positive rates across groups; others require equal calibration. Impossibility theorems prove that, except in trivial cases, these definitions conflict. Choosing among them is inevitably a moral and political act disguised as a technical one.

“Fairness is not a coefficient you optimize; it is a conversation you continue.”

Organizations that skip this conversation often end up in reputational quicksand. The ethical path forward begins by asking impacted communities which harms matter most, then translating those values into measurable constraints.

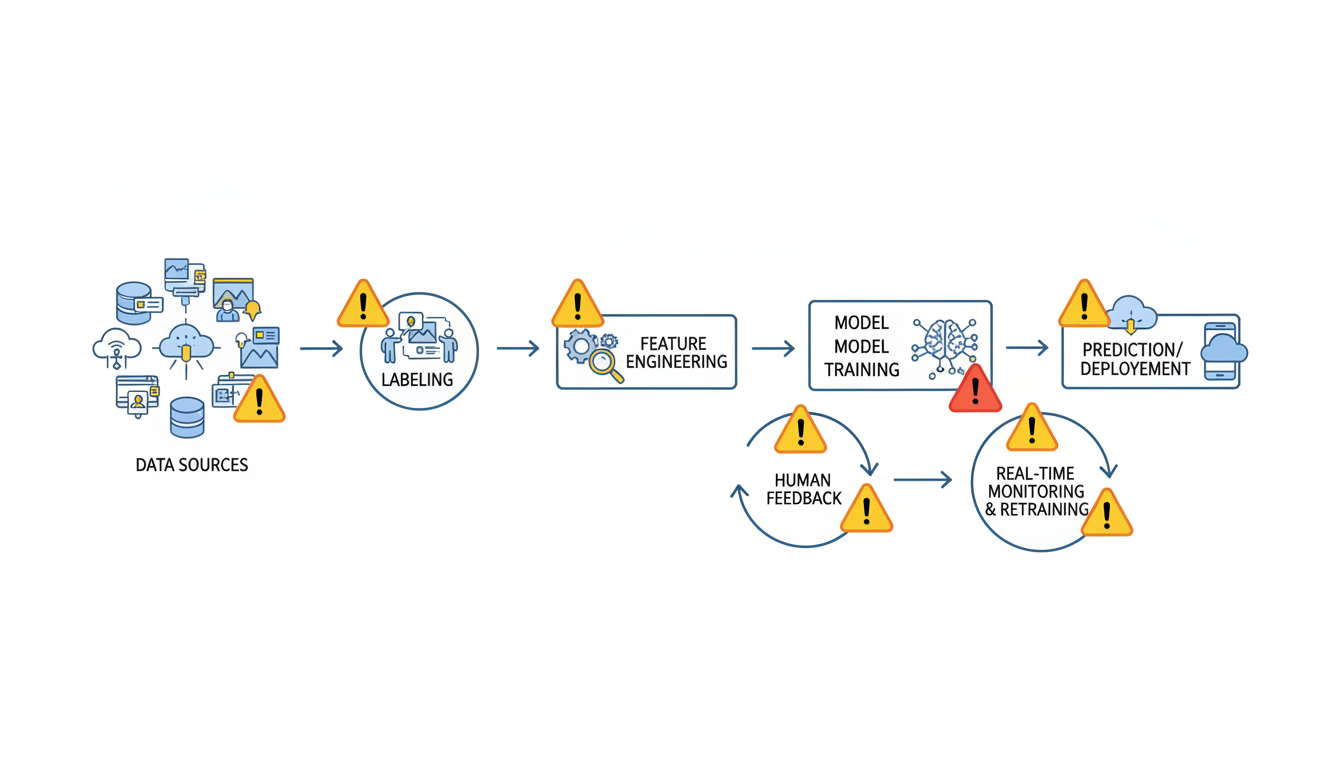

3. The Pipeline of Prejudice: Where Things Go Wrong

- Data Collection: Under-represented groups produce fewer digital footprints, leading to “invisible” minorities.

- Labeling: Crowd-workers bring their own stereotypes when tagging images or rating “toxic” speech.

- Feature Engineering: ZIP code can proxy for race; shopping history can reveal pregnancy status.

- Model Selection: Complex black-box models may amplify spurious correlations that simpler models would ignore.

- Deployment: Feedback loops—such as predictive policing sending more officers to already over-policed areas—cement inequity.

4. Tools You Can Use Today

Perfection may be unattainable, but improvement is measurable. Practical interventions include:

- Bias dashboards: Open-source libraries like IBM’s AI Fairness 360 or Fairlearn provide disparity metrics out-of-the-box.

- Adversarial debiasing: Train a second model to “audit” the first, penalizing predictions that reveal protected attributes.

- Synthetic data augmentation: Generate artificial samples to balance historically marginalized groups, reducing sampling bias.

- Human-in-the-loop review: Randomly escalate high-stakes decisions for human verification, creating a natural experiment to audit model behavior.

Remember to document everything. Model cards and data sheets that report known limitations turn transparency from a slogan into an engineering deliverable.

5. Governance: From Slack Channels to Boardrooms

Technical fixes alone won’t suffice. Ethical AI requires governance structures that can say “no” to profitable but harmful products. Leading practices include:

- Cross-functional review boards with veto power, including ethicists, domain experts, and community representatives.

- Algorithmic impact assessments conducted before deployment, akin to environmental impact reports.

- Whistle-blower protections for engineers who spot discriminatory outcomes.

- Regular third-party audits whose findings are made public, not buried in appendices.

Regulation is catching up. The EU’s proposed AI Act classifies high-risk systems—such as biometric identification or credit scoring—and mandates conformity assessments. Forward-thinking companies are drafting internal standards now to avoid a last-minute scramble.

Conclusion: Bias as a Living Metric

An algorithm free of prejudice is less a destination than a horizon we navigate toward, constantly recalculating as social values evolve. The goal is not flawless code but accountable processes: measurable fairness targets, transparent trade-offs, and empowered communities who can demand redress when systems fail. If we treat ethics as a user requirement—tested, versioned, and refactored—we can still harness AI’s power without hard-coding yesterday’s injustices into tomorrow’s institutions.